In Poland, disability – just like the owls in Twin Peaks – is not what it seems to be. It is the same with Joanna Pawlik’s exhibition, hosted by the Bytom Kronika Gallery, where the Red Room – inspired by Lynch’s series – is not inside the Black Lodge.

Instead, it is Black Pasta – a fragment of Joanna Pawlik’s “I wonder...” show – which is inside the Red Room. The show, consisting of songs created and performed by people with disabilities, is another opportunity provided by the artist to one of the least audible, excluded group. The narrative of the exhibition is based on its individual fragments.

The “Black Pasta”, served as a side-dish, is in the central point of the Lynch-like room – in a black circle, like in the anus from which it was “born” in a dream of one of the performers, Edek Gil-Deskur. That onirist experience triggered the creation of an improvised text – a painful description of economic redundancy and the overwhelming depression caused by unemployment. The solution is found in the abject act of excreting pasta, which – similarly to having one’s own business, so desired in the times of economic transformation – guarantees an instant access to all the joys of capitalism. The underlying context is obviously the grim financial situation of people with disabilities in Poland. The lack of systemic support is another area of the inept state policy, camouflaged by a false narrative of good change and economic Eldorado. For Edek, the so longed-for economic success, impossible to achieve by the majority of Poles, let alone the disabled citizens, is not just a chance for financial comfort. It means much more: a secure family and the end of rejection. The vision in which excreting the “product” from your organism solves problems associated with malfunctions of your body reverses the reality and leads to purification. The feeling of one’s own abjection turns out to be a gesture of emancipation.

The abject may become a particular sign of presence. While maintaining the participatory mode, Joanna Pawlik first and foremost creates the expression platform for the people she cooperates with. She invites them to share a table with every guest having identical rights. At the same time, the author steps back, letting the co-creators lead. She appears at the exhibition directly only once to present a sculpture imitating the leg she lost when she was 10.

Locked in a showcase, the amputated child’s leg becomes the author’s signature and the clou, main dish of the display. Existing through being lost. Being a body which cannot achieve full satisfaction and remains in the state of permanent unfulfillment. Just like in the angry “Cry for a relationship” by Wiktor Okroj, where the author bluntly confesses his inability to achieve the emotional and sexual gratification. Imprisoned in the consistently rejected body, the only response he can get is to “fuck off’. In the Polish reality, struggling with any sexuality, this disabled body is all the more deprived of any sexual context, stripped of adulthood and the natural need of sexual passion. Instead, to remove the problem from sight, it is kept being clothed in naive childishness. But the problem does not disappear. That leads to great frustration which the body cannot fully express. Initially, Wiktor’s words are almost completely incomprehensible. It takes one some effort to discern them, although much less than it takes the author to utter them.

The same type of challenge is associated with experiencing the “Marathon” by Klaudia Kwiecień - presented in the next room. The recording of a text – starting as a melodic recitation to be finally shouted out – about the effort necessary to do a trivial activity is accompanied by a working treadmill. Here, the viewer’s body is invited to make the effort of “identification” and leaving its comfort zone to get sweaty and feel breathless, dizzy and dry in the mouth. This experience, rather untypical of art gallery, simulates the everyday reality of a body subjected to an incessant struggle for ability. The author’s world is a race fraught with architectural, cultural, social and, just like in Deskur’s “Black Pasta”, family obstacles.

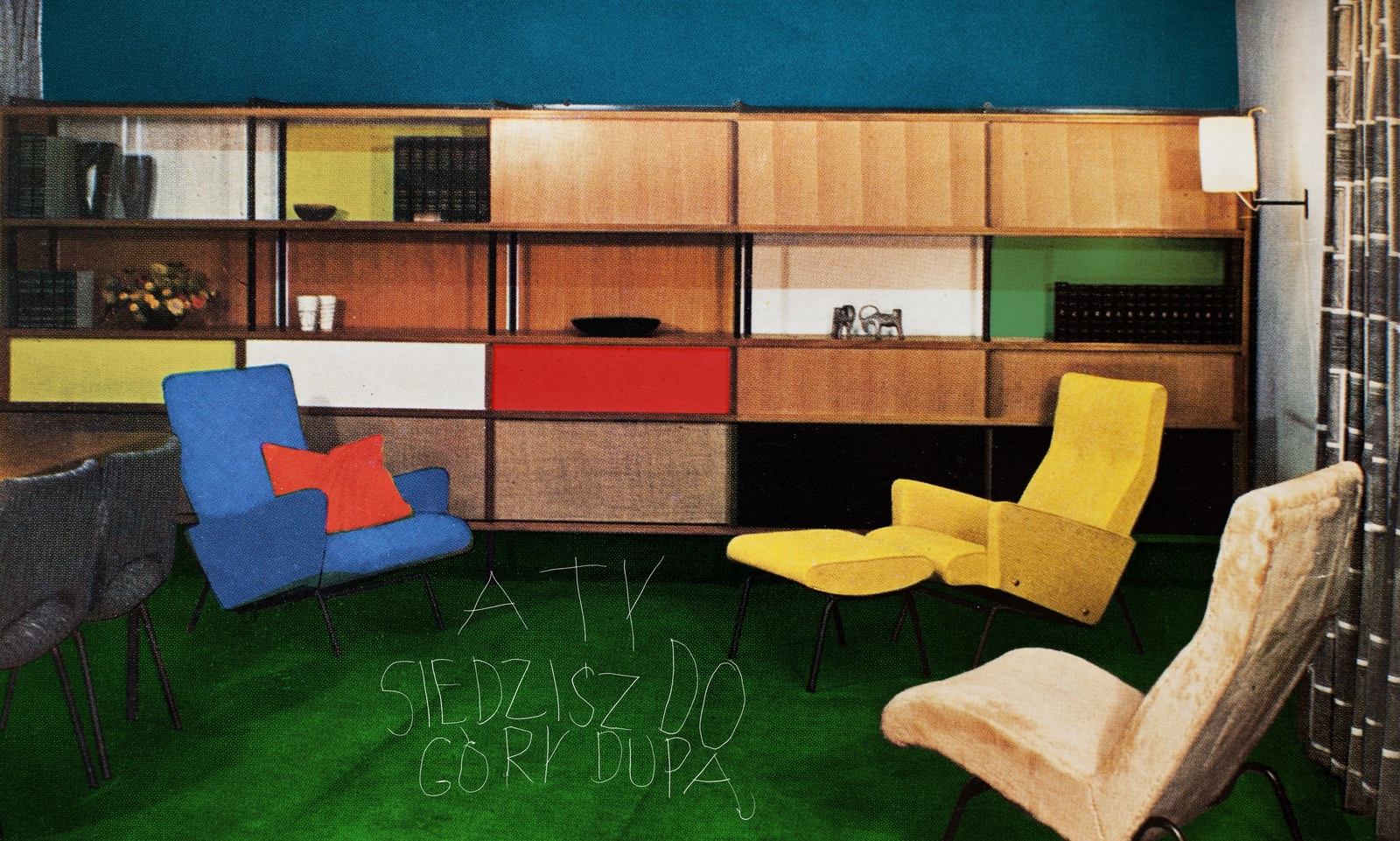

Usually, the problems stays within those four walls where Joanna Pawlik places us in her cycle of lightboxes. The French graphic works, showing aestheticized interiors from the 1960s, are contrasted with texts looking as if they were written by a child. In western narratives, the 1960s are a family idyll of clear sexual and social roles. It is into this very reality that Pawlik introduces brutal words, spoken to a disabled daughter by her mother. One of the strongest and still unbroken cultural taboos is the taboo of the child-repulsing mother. This is why the figure of the antagonist stepmother, so fundamental to a number of fairy tales is in fact not so much a bad wife as a villainous mother. It is easier to accept harm inflicted by an unrelated hand. However, while this fairy-tale rejection by the mother-stepmother stems from jealousy and symbolizes the psychoanalytically defined emancipation of the Self, in Joanna Pawlik’s lightboxes the child is rejected merely because of her “faultiness”, and the mother becomes a devourer– taking away the child’s subjectivity and always rejecting.

The pasta seems to be endless and does not leave any room for dessert. Also endless are the political matters: the body, motherhood, disability, eating and most of all, craving. “Black Pasta” is predominantly a story of craving which hurts and castrates one your opportunities. Ultimately, it is the craving for safety, acceptance and affection. It is the realization of being abandoned by your mother. Or your motherland (if we wanted to feminize the word fatherland). There, the people with disabilities, like anyone who departs from the increasingly exclusionary norm, are thrown into a common category of “otherness” – deprived of their names, faces and personal stories. Joanna Pawlik allows them to tell their own narratives which demystify the fiasco of the thoughtlessly cherished system, offering ever simpler menu, composed of increasingly poorer products.

- Publication

- Text

- February 2020

- author: Kamil Kuitkowski

- text accompanying Joanna Pawlik's exhibition Black Pasta